Playing Chopin

Published July 27, 2023

The first “serious” piece I learned for piano was Chopin's Prelude in E minor. It is a languid, lyrical piece, short and quiet with a distinctly funerary air. My edition was entirely unsuited to the emotional quality of the pieces, with a neon cover and a garish, fading blackletter announcing the composers name and the comparative difficulties of the pieces inside.

I took to it quickly. I remember sitting there, timid, at the piano bench, fearing that the downstairs neighbors might make the dreaded call diplomatically articulating their concerns about soundproofing, or that I wouldn't be able to read the music at all. And yet, in two weeks, I could manage to push through it, gingerly tapping the keys for fear of disrupting the balance my teacher had emphasized, and utterly engrossed in the contour of the melody, the virtuosic (at that time, at least) climax, and that then-terrifying cadence.

I was fourteen then. I am not a musical prodigy, and talk of “talent”, of “natural gifts”, then and now, makes me uneasy. Those early steps - posture, playing scales, the rudiments of reading music - had to be coaxed out of me over the course of many miserable lessons and exhausted teachers. The courtesy of those young men and women - to deal with a 9-year-old just now encountering the shocking fact that there were things he was not good at - astounds me to this day. My early musical education was brief and difficult.

Despite this, I still returned to the piano as often as I could. I would sit and press the keys, convinced that I could stumble into the music that lay just out of reach. I would sit, as the emotions bubbled up, and improvise endlessly, holding down the sustain pedal for far too long as I played chord after chord. The colors and textures I couldn't quite reach — the lush extensions of jazz ballads, the virtuosity of a romantic etude, the intricacies of a four-voice fugue — tormented me, heard and felt but never embodied.

In 8th grade, brimming with trepidation, I decided to try again. I learned the basics of theory and played pop songs off ad-ridden guitar chord websites. I wrote a bit too: a Klezmer piece, the odd duet for two violins, a pop song. I wrote for myself, playing with the sounds I was beginning to discover. I didn't know how, really. I broke every rule in the book, my output was formless and dissonant. The occasional exciting idea broke through, but it was soon reclaimed by the waves of what I retroactively learned were Tristan chords.

Yet, there was something there.

My parents, ever supportive, insisted on showing my score to as many people as possible, and I got a surprisingly positive response. It satisfied something deep in my psyche, the stream of positivity for something I created. I felt empowered, enthusiastic, and the seed of an ambition formed in my mind. I would become a composer. I would study at a conservatory, play and learn intensely, and share my “gift” with the world.

This period of my life didn't last long. When I was twelve or thirteen, my grandfather passed away. It was a cruel death, the sort that leaves a bad taste in the mouth and a hole in the heart. He was in decline for years before it, the sparkle in his eyes, his quick wits, slowly replaced by an incoherent discontentment. It terrified me — the fear of fading, of forgetting — overtook my mind in its way.

It took a long time to find the piano again.

Which brings me to that room, fourteen years old, at my first lesson, when my teacher asked me to sightread the prelude. I couldn't do it that lesson, but after two weeks the prelude took shape.

I could play that notes, at least. Balance, articulation, rubato — these things escaped me for a long time. But the spirit of it! That fiery humanity! That acute sense that my emotions had been perfectly understood! Needless to say, I started listening to more Chopin.

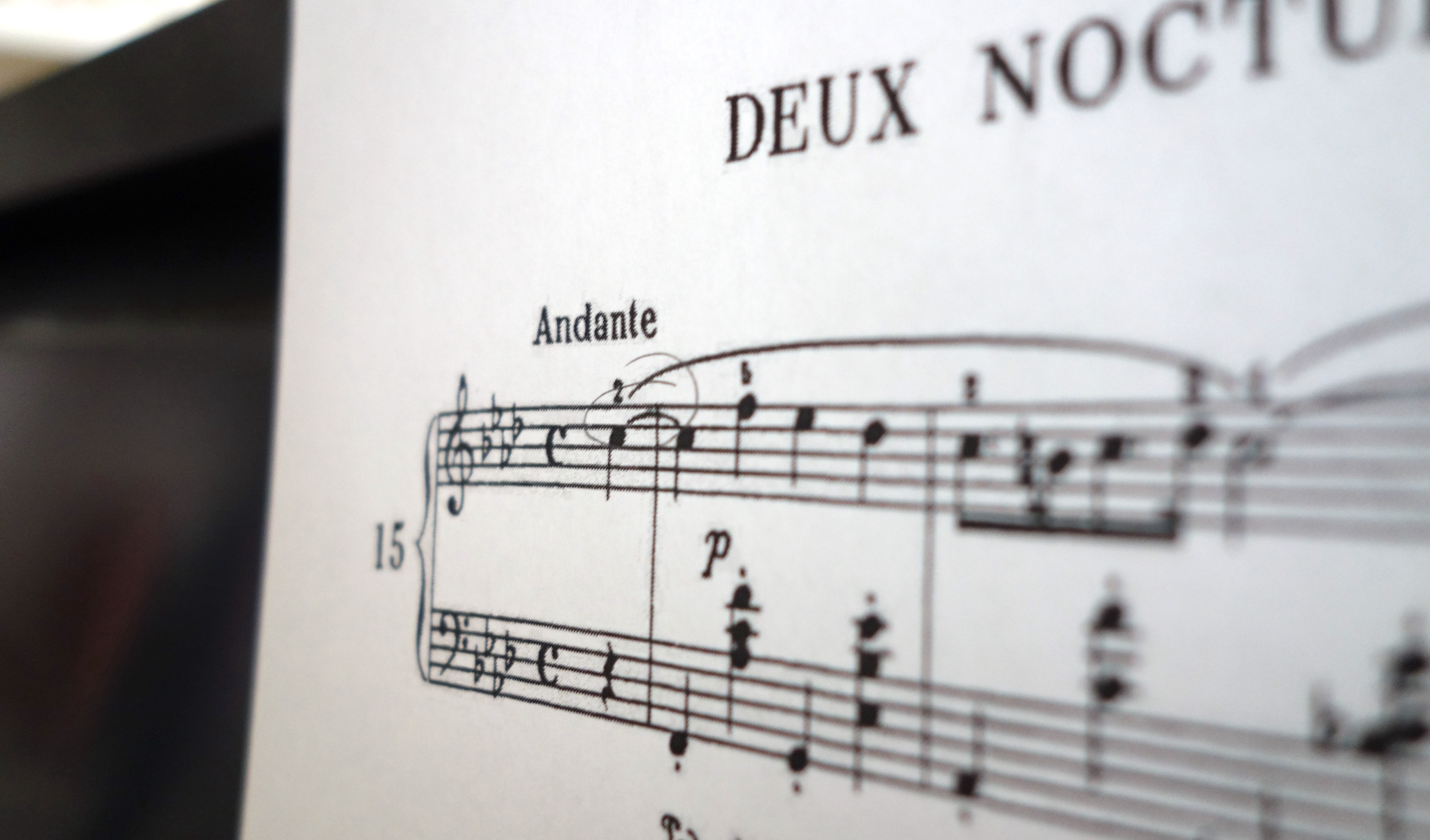

The next years of my musical education, interwoven as they are with the epidemic, are a blur in my mind, reduced to a series of Panglossian vignettes. A stately practice room at the music school, dying light gently illuminating an ornate piano, as I played the last page of the Eb major nocturne. An odd sleepless night, alone and desperate, quietly sight-reading the A minor waltz. The catharsis, the overwhelming sense of victory, as I finally played the first few measures of Fantasie Impromptu. These moments will always have a place in my heart.

I was once rightfully criticized by my teacher for playing to heavily to my own aesthetic preferences. My exaggerated ritardandos, my self-aggrandizing crescendos, they serve the player but not the listener. Chopin is so easy to put everything into; the bad days at school, the bad days at home, the overwhelming feelings of rejection and isolation, all overtake common interpretation and turn a Ballade it into an unrefined rant, this Platonic ideal of emotional expression made into an ugly, all-to-real expression of the inner thoughts of an angst-ridden teenager.

Chopin bore the weight of everything I had to say, but couldn't. In Mazurkas and Preludes I found outlets for failed relationships and broken dreams. In Nocturnes, for this restless yearning for everything I sorely lacked. I was so sure that I knew him, this chronically ill, awkward man, equal parts ambitious and isolated. In Ballade No. 1, in Sonata No. 2, I was sure I could hear the sounds of a deeply broken man, the soaring highs coming only out of a desperate desire to claw out of an emotional pit.

I'm doing better now, I think, and Chopin has taken on a very different character for me. I started to recognize the genuinely joyful parts of his music — the second section of Mazurka in G Minor comes to mind — and realized that I had been a bit reductive. Not all of these expressions could be derived from sorrow alone. I had begun to think of him, I suppose, as doing as I was — spilling and spreading his emotions onto the page as they came — and that those beautiful forms and intricate chromatic melodies simply emerged from an inherently tasteful mind.

I don't think this is true anymore, or at least not completely. Chopin was, despite (or, perhaps, in accordance with) tragedy, a composer, a craftsman assembling delicate parts. It's been a difficult journey coming back into accordance with this simple fact. Chromatic runs are no longer played so “expressively” as to be incoherent. Cross rhythms are studied, not “felt out”. When I see an emotionally heightened passage, I try to consider the nuances of the passage, the power of restraint, and work to not “let go”.

Mostly.

Bach is like an astronomer who, with the help of ciphers, finds the most wonderful stars. Beethoven infuses the universe with the power of his spirit. I do not climb so high. A long time ago, I decided my universe would be the soul and heart of man.